Freedom of a Thick Self/Identity Must Always Exist within a Stable Matrix

In this post, I want to emphasize some of the important parameters or context (situatedness) of freedom. How do we make best sense of healthy, wholistic, robust freedom and choice? This has become the vital point of tension in our discussion of The Wisdom of Charles Taylor in this series of twelve posts—a thought experiment riddled with a sense of urgency for contemporary life. With Taylor, I have been addressing a crisis at the heart of Western culture (loss of moral soul, virtue, and character), and working towards a vision for cultural renewal through the recovery of the language and culture of the good. It is absolutely vital to our wellbeing and our common future. The character of freedom is key to how the game of life gets played. Imagine, for example, hockey with no rules or referees, where every player maximizes their selfishness. Freedom without guardrails/values/virtues, without context, is no freedom at all, but rather more like chaos. It too often leads to oppression and exploitation, loss of rights and freedoms, and a smaller self. We are in the discourse of constitutive or metabiological knowledge, which speaks of an interconnected skein of meanings which define the shape of human significance (C. Taylor, 2016, 253). In this dynamic, there exists an interwoven set of enactments (behaviour), articulation (words and symbols), and interpretation (hermeneutics of the moral self). Our emotions are implicated as well, for when moral wrong is done to us, we suffer much pain. When moral integrity and courage are displayed, we are inspired, empowered, and heartened. Taylor intones: “I have integrity when my words and action cohere, when I pursue what is really important without suffering deviation or distraction from irrelevant issues or contrary desires…. Integrity bespeaks wholeness, unity.” (C. Taylor, 2016, 230). Clearly, morality requires infrastructure. The statement below is composed partly of warning and optimism about a way forward. We must choose wisely as we traverse late modernity.

In his important book, Hegel and Modern Society, Taylor (C. Taylor, 1979, 154-66) addresses the critical need to situate freedom properly in order to avoid a radical, destructive abstraction. This critique of Hegel applies to our quest for a redeemed freedom. His tough question is: “What should a society of freedom look like beyond an empty formula?” (C. Taylor, 1979, 155). As I have argued in this series, he longs for us to see the meta-perspective: the larger context of the individual choosing agent. Taylor raises some important issues and questions concerning the healthy situatedness and relationality of freedom. In his analysis of freedom in the late modern world, Taylor calls into question the validity of a radical freedom as self-dependence or self-sufficiency. This view is very common in economics and society today. Taylor does not find it surprising that we continue to value freedom as some sort of ideal: “[Freedom] is one of the central ideas by which the modern notion of the subject has been defined, and it is evident that freedom is one of the values most appealed to in modern times” (C. Taylor, 1979, 155). But he would argue that freedom needs a context with definite parameters/guardrails. There must also be content and substance in our definition of freedom in order to move beyond an ideological mystification of a rather raw, rebellious, narcissistic, revolutionary project. It does not exist by and for itself just as a beautiful, shining idea for a placard or a mythos to make us swoon or take up arms. This is idolatry. Pure freedom without limits (absolute freedom) is nothing; it is chaos; it is no place. “Complete freedom would mean the abolition of all situation.” says Taylor (C. Taylor, 1979, 157) and that renders it rather absurd. It is only negative freedom from, without its positive counterpart (Isaiah Berlin, Timothy Snyder) freedom for. Taylor’s analysis cuts through the naiveté and the mythology of an aesthetic idea of freedom like that of Michel Foucault. We should be alert, as Canadian public intellectual Jonathan Pageau says, that many contemporary aesthetic ideas can contain a Luciferian edge.

Taylor seeks to transcend the illusion of the sovereign self in command of the world by situating it in a world both larger than it and partly constitutive of it. He employs hermeneutics. He does this by striving to articulate for us those elements in the self and its circumstances that come closest to expressing what we are at our best, highest form of humanism. The most expressive articulations are not simply the creations of subjects, nor do they represent what is true in itself independently of human articulation: “They rather have the power to move us because they manifest our expressive power itself and our relation to our world. In this kind of expression we are responding to the way things are, rather than just exteriorizing our feelings” (C. Taylor, 1978). Thus, he reinforces this idea of moral realism. We must make sense of our choices within our whole context, to discern rightness or appropriateness of actions, the implications of our choices on others, and especially the marginalized, weak, or poor. What is required for robust, free agency, moral subjectivity, and healthy moral self-constitution?

The Hermeneutic

Much philosophical reflection in the twentieth century has engaged the problem of how to get beyond a notion of the self as an abstract, self-dependent will. One wants to bring to light its insertion into nature (one’s own and those which surround it), plus the context of one’s narrative history. Taylor is arguing that the situationless, transgressive notion of freedom, as a political modus operandi in Western history, has been very destructive, insensitive to larger context, other stakeholders, and to the past. He gives examples such as the Bolshevik voluntarism, a movement that crushed all obstacles in its path with extraordinary ruthlessness, or the Reign of Terror which was part of the French Revolution, both motivated by the “clarion call of freedom” (C. Taylor, 1979, 157). History bears out the strong temptation to forceful imposition of one’s final liberationist solution on an unyielding population, with untold violence unleashed in the name of radical, aesthetic-freedom. Freedom can be anti-human: Too often, poets have endorsed these brutal and bloody revolutions. As history has shown, the tendency is for the liberator to become the next oppressor. Freedom without context most often becomes a dangerous ideology, or idolatry (see William Cavanaugh’s critique of nationalism in The Uses of Idolatry, chapter 6., 217-79)), which justifies even the most brutal means to its ends. It calculates as a mythos, one that can be manipulated by persons with a wide variety of nefarious motives and goals. Unbounded, revolutionary freedom remains intensely problematic and dangerous. Marxism has often displayed this ‘burn it all down’ approach to social change.

Neither happiness nor pleasure, freedom nor justice could be identified or understood under the condition of no boundaries, or where freedom is simply defined as the radical transgression of boundaries, rather than true cultural critique. Taylor (C. Taylor, 1979, 157) notes: “Complete freedom would be a void in which nothing would be worth doing.” The tradition of freedom as autonomy and self-sufficiency is riddled with problems. The notion is that freedom should be “endlessly creative” (C. Taylor, 1979, 155). Isaiah Berlin spoke of both positive and negative aspects of freedom. In these solely negative characterizations of freedom (freedom from restriction), what occurs is the tendency to think away the entire human situation and to substitute an abstract, fantasy world where one could be totally free. It tends to manipulate and divide people, and leads to autocracy and oppression–losing freedom for all except a few elites. When we apply this to corporations, we see the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer, producing the dangerous great economic divide in society. The market in the end will not make you free.

Unrestrained, self-determining freedom can often be empty freedom (a precarious sort of autonomy) leaving a vacuity longing to be filled by almost any moral trajectory, constructive or destructive: community development or narcissistic self-indulgence, compassion or violence, character development or self-trivialization, militarism or peace-making reconciliation. For example, self-disciplined freedom has been applied to ethnic cleansing, to expulsion of people from their land, or to slavery, torture, and terrible violence. It is irresponsible to be unconcerned about the outcome of an open-field freedom doctrine. Freedom without context, without ethics, and without a relationship to the good easily leads individuals towards celebrating their own power and using it destructively, not for the common good. Could anything be more well-illustrated from some of the social and political experiments of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? Many volumes have articulated the problem on this subject.

According to Taylor (C. Taylor, 1979, 151-58), the trend toward this negative understanding of freedom comes from four key moves. It involves a decontextualization, a shaking loose of the individual self from definitions of human nature and from the natural world, the cosmic order, social space, religion, and history. This entails a serious form of self-wounding, self-depreciation.

Four Moves

Move a. The new identity of a self-defining subject wins by breaking free of the larger matrix of metaphysical, cosmic or societal order with its claims of the value of mutual accountability. In this case, freedom is defined mainly as self-sufficiency and self-dependence. It entails the process of defining an experimental self, a reconstructed or re-invented self.

Move b. Human nature has to be re-invented, reshaped in order to access unrestricted/unshackled action and self-expression. It is highly performative and can be very aggressive. One tries to remove all obstacles to freedom of expression, which are seen as various forms of oppression, domination, and harm to the self.

Move c. The uncensored individual indulges in a celebration of the Dionysian expressive release of instinctual depths, the sensuous, the violent, the rapacious. This revolutionary thinking is partly sourced in the dark work of the Post-Romantic, anti-humanist philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and his followers.

Move d. Finally, this trajectory involves the death of all traditional values (humanist, Christian, Kant’s moral imperative, ideals from other religions), and entertains the belief that ethics is rooted in nothing but the will-to-power. It is the death of principle, virtue, and high character. One is accountable only to oneself, and thus there can be no such thing as responsible citizenship, or the obligation to the common good.

Consequences of These Radical Moves

a. Self-trivialization results in an egoistic, hollow, characterless person with no defined purpose and no ability to discern between good and evil, right and wrong, justice and injustice. Human rights are not respected when the goal is revolution.

b. One loses the ability to discern between one’s various conflicting desires: between destructive, neurotic compulsions, fears, paranoia, and addictions, over against high and noble instincts for the good of the other/society, justice, peace, humility and personal integrity. Malevolence mixes with charity in a duck soup causing moral confusion and angst. It is very difficult to make sense of such a person’s behaviour. Volatility is the order of the day.

c. The Trap: Despair can take over one’s psyche due to the loss of a larger horizon of meaning. Indeed, it can become a kind of dialogue with the devil. Inventing one’s own meaning and the reshaping of oneself is hard, a heavy burden—involving a lot of pressure (Jonathan Haidt, The Anxious Generation). Despair illness is a major problem in Western countries today.

d. Relationships take a hit because this whole approach to life does not celebrate the spirit of interdependency which is essential to community and communion. There is little emphasis on complementarity, or hope of forgiveness and reconciliation. The tendency is to blame others or the system for one’s or society’s problems.

Foucault’s late period (third oeuvre on care of self) is a good example of this phenomenon. Taylor writes:

Foucault in an important sense was a philosopher of freedom … that is, he was a philosopher who claimed to unmask and lay bare domination, the interiorization of power relations by victims, and although he often claimed that power had no subject he certainly portrayed it as having victims … The moral thrust of these analyses … was implicit in the language in which it was cast. They called for opening a line of resistance for the victim, a disengagement from the full grip of the current regime of power, particularly from its hold on our self-understanding. Foucault’s own intervention in politics and public life … bore out this interpretation … in his History of Sexuality 2 & 3 and latest interviews, he made clear his view of freedom, the building of an identity relatively uncolonized by the current regime of power. (C. Taylor, 1999, 115)

The goal seems to be one in which the person or group concerned will have achieved full autonomy and will no longer be controlled or influenced. No place is allowed for another possible telos of the struggle, one in which the agents or the groups, previously related by modes of dominance, might reassociate on a better basis of mutual interest. The invocation of the victim scenario is a very common move in a position of this type. The history is usually articulated in such a way as to make it almost inconceivable that there be a new mode of association, let alone that both sides need it to be complete beings.

Taylor, on the other hand, attempts to situate the self and subjectivity in a healthy context by relating it to life as embodied social being (Merleau-Ponty), connected to nature (without reducing it to nature) and history (again without reducing it to history). He argues strongly that one needs to see freedom within the context of a situation. Ethics, purpose, and moral agency, in his mind, are embedded in a social network, a community, in a narrative history. It was not always incumbent to see the self as autonomous individual making choices, designing oneself in a protective stance over against a hostile world or oppressive code of ethics. Based on his proposed realist moral ontology of the good, Taylor is motivated to reveal the problems with radical definitions of freedom as self-dependence rather than interdependence. They cannot sustain societal harmony or promote the common good. Freedom as escape must be subverted by freedom as opportunity or calling within community. The situated notion of freedom sees free activity as grounded/and nuanced in the acceptance of one’s defining situation, together with its limits, possibilities, and accountability–significant texture. One has to keep one’s promises and fulfil one’s obligations.

Finally, Taylor offers insight on freedom’s situatedness from another angle. He contests Foucault’s idea that freedom can be reduced to a set of limits to overcome, with only a vague, undirected creativity towards a beautiful self or the beautiful life. A skeptical freedom that limits itself to talk of new possibilities for thinking and acting, but heroically or ironically refuses to provide any evaluative orientation as to which possibilities and changes are desirable, is in danger of becoming merely empty or worse (predatory and malevolent). According to Taylor’s view, the individul flourishes in freedom when she pursues the good, is transformed by the good, within a context of community, and a coherent narrative identity. Freedom within this context allows the self to engage the social situation in a fruitful way. There must be a space where liberty can be secured and positive relational potential emerges, an atmosphere of trust and accountability. Taylor strongly cautions against reductive theories of freedom and the self. He says that one needs a “more articulated, many-levelled theory of human motivation” (C. Taylor, 1979, 160). He welcomes the full complexity of moral self-constitution, and does not want to leave out anything that is actually operative in healthy moral agency or in the full horizon of morality. Freedom without context (negative freedom) does not calculate as responsible freedom; it ignores the value of others as a significant part of ethics and is too narrowly focused on one’s relationship with oneself, and the development of one’s own project or ethos.

Applying Hermeneutics: The text of self and the text of freedom need a context, the motivational economy of the good. For Taylor, this context is the horizon of the good, including divine goodness, incarnational spiritual culture, and agape love. “All zero-sum views of divine and human freedom—views that assume the two are inherently competitive—will also be put in question; divine freedom will be reimagined as freedom for the love and freedom of the other.” (J. Begbie, Abundantly More, 2023, 154) Within this economy, the other reappears as a significant and positive contributing actor in one’s moral life. They are not the enemy to be feared or hated. It increases one’s capacity to see the human reality, value, and dignity of others, especially those who are different from us. For example, people like King, Ghandi, Mandela, and Jesus free us to be ‘for’ the other and free us ‘from’ the fantasy of being totally independent. See especially Taylor’s chapter fifteen, “History of Ethical Growth” (C. Taylor, Cosmic Connections, 2024, 553-587) for a deep analysis on this subject.

Taylor strongly believes that it is possible to win through on both freedom and responsibility (citizenship), mutuality and complementarity, reconciliation and healing of human trauma and brokenness. “The biblical New Testament testifies to this ceaseless pressure outward, to a momentum of love that exceeds the bounds we often assume determine and restrict our lives—it is potentially unstoppable in its effects. Koinonia reveals a non-possessive, non-contractual way of life.” (J. Begbie, 2023, 156). Divine love operates out of an abundance of generosity. To come to Christian faith is to participate in the mutual love of Son & Father: we are impelled to give ourselves to one another, because the love of the Father energizes us. Within this high dialectical relationship to the good, a person can establish deeper relationships and build mutually supportive, loving accountability and security. Tylor holds that this more rooted, embedded (thick) individual self will show more resilience and stability under stress, while enjoying wholistic freedom as it discerns its calling and meta-biological meaning. “We are invited into a momentum that enables us to delight in our God-given creatureliness, to flourish as creatures through an expansive relation with God—one of dispossession, of giving toward, and giving away” (J. Begbie, 2023, Ch. 8). The need remains for a more full-blooded conception of subjectivity (soul recovery) within the parameters of the moral horizon, the hypergood, narrative, and calling within community. Community of the right sort is at the heart of true freedom. Perhaps this will also lead to a higher, fuller, wiser, truer form of human life.

Economic Application

- Successful economies are not jungles but gardens–they must be tended with care.

- Inclusion creates economic growth and social harmony.

- The purpose of a corporation is not to merely enrich shareholders or the corporate elites.

- Greed/selfishness/hoarding is not good. Sociopathic behaviour is bad for business in the end, and lands some CEOs like Bernie Madoff in jail. It can lead to terrible fraud, destroy a business, or bring down a government.

- A new narrative is emerging from roundtables and think tanks around the world. It is one that improves the welfare of more stakeholders (workers, customers, the community, shareholders) and cares for the environment. It is good for all players in the economic game of life, and improves civil society–builds for the long term. See S. Keen, The New Economics.

- Empirical research shows that humans are quite cooperative, reciprocal, intuitively moral creatures with a healthy sense of responsibility for others–this outlook leads to prosperity and human dignity.

- Virtuous economies round the globe are innovative, solve problems, and involve more complex forms of social and economic cooperation. Is this not the way of wisdom and high culture?

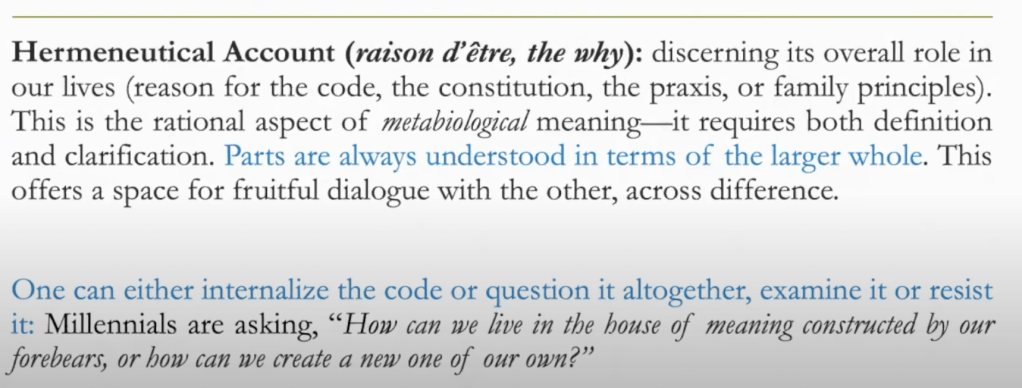

The Hermeneutical Way of Seeing the World

The working assumptions of this approach includes European philosophical voices like Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Gadamer, the later Wittgenstein, Charles Taylor and Jens Zimmermann. We find this approach a balance to Anglo-American Analytical philosophy (the epistemological approach). The connection between the individual self and the world is an I-Thou relationship.

- Self is not the first priority: the world, society and the game/drama of life come first. We only have knowledge as agents coping with the world, and it makes no sense to doubt that world in its fullness. Taken at face value, this world is shot through with meaning, purpose, and personal discovery.

- There is no priority of a neutral grasp of things over and above their value. It comes to us as a whole experience of facts and valuations all at once, interwoven with each other.

- Our primordial identity is as a new player inducted into an old game which continues from ages past. History is important. We learn the game and begin to interpret experience for ourselves within a larger communal context. Identity, morality, and spirituality are interwoven within us and within the dynamics of life. We sort through our conversations, dialogue with interlocutors, family, and friends, looking for a robust and practical picture of reality that makes sense.

- Transcendence or the divine horizon is a possible larger context of this game. Radical skepticism is not as strong here as in the epistemological approach. There is a smaller likelihood of a closed world system (CWS—closed to transcendence as a spin on reality) view in the hermeneutical approach. In a sense, it is more humble, nuanced, embodied, and socially situated/embedded (Merleau-Ponty).

- Language use is the Expressive-Constitutive type (Herder, Hamann, Humboldt, Gadamer, Taylor) The mythic, poetic, aesthetic, and liturgical returns. Language is rich and expressive, open, creative, appealing to the depths of the human soul. Language is a sign. Language helps us create world.

- Moral agency is revived within a community (oneself as another as in Ricoeur) with a strong narrative identity, in a relationship to the good, within a hierarchy of moral goods and practical virtuous habits that are mutually enriching and nurturing. One is more patient with other people, the stranger, the person who is different. Hospitality wins out over hostility.

- The focus of human flourishing is on how we can live well, within our social location—a whole geography of relationships that shape our identity, and which we in turn shape as well. This is a thick version of the self, open to strong transcendence, within a meaningful whole.

Gordon E. Carkner, PhD, Author, Blogger, YouTube Webinars & Lectures, Meta-Educator with UBC Postgraduate Students & Faculty

Bibliography

Applebaum, A. (2024). Autocracy, Inc.: The Dictators Who Want to Rule the World. Signal McLellan & Stewart.

Begbie, J. (2023). Abundantly More: The Theological Promise of the Arts in a Reductionist World. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

Carkner, G. E. (2024). Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture: Grounding Our Identity In Christ. Wipf & Stock Publishing.

Carkner, G. E. (2016). The Great Escape From Nihilism: Rediscovering Our Passion in Late Modernity. InFocus Publishing.

Cavanaugh, W. T. (2024). The Uses of Idolatry. Oxford University Press.

Keen, S. The New Economics.

Snyder, T. (2024). On Freedom. Penguin Random House.

Taylor, C. (1978). Language and Human Nature. Plaunt Memorial Lecture, Carleton University.

Taylor, C. (1979). Hegel and Modern Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, C. (1999). In J.L. Heft (S.M.). (Ed.). A Catholic Modernity? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, C. (2016). The Language Animal: The Full Shape of the Human Linguistic Capacity. Harvard University Press.

Taylor, C. (2024). Cosmic Connections: Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment. Harvard University Press.

Dennis Danielson grapples with morality in response to C.S. Lewis’s classic, The Abolition of Man https://ubcgfcf.com/2019/01/27/dennis-danielson-grapples-with-moral-discourse/z0000008/

YouTube Video

Leave a comment