Agape Love, Ethics, and the Transcendent Turn

So, I have been writing about epiphanies of transcendence in the previous post. Here I want to build on that concept. It takes us into the economy of grace which is captured in the Christian term in Greek: agape love. Agape exceeds the bounds of reciprocity; it cannot be defined in terms of prescriptions for self-realization or self-interest alone. In this love, we find the self involved in a transcendence of the strong variety. But when this grace disappears, coercion, contempt and terror sometimes flow in to take its place. Dostoyevsky makes a very interesting connection between self-hatred and terror in the previous discussion (Post 14). The Foucauldian autonomous self takes a stance over against society and the other, a stance of resistance and self-protection, attempting to discover dignity in precisely this manner which Dostoyevsky discourages, of separation from the world. This explains the willingness of the aesthetic self to take responsibility for itself, but its unwillingness to take responsibility for other people and the common good. Some top authors who write clearly about agape are Glenn Tinder (The Political Meaning of Christianity), Larry Siedentop (The Invention of the Individual), and David Bentley Hart (Atheist Delusions).

Charles Taylor’s recovery of transcendent moral sources ultimately implies an opening of the self to something outside that empowers the self. This larger horizon could give enhanced perspective and positive energy to Foucault’s artistic self-creation. In fact, it does rethink his modern doctrine of self-creation/self-definition. Foucault is open to the epiphany of self within a self-reflexive horizon, but does not access, was not open to, the epiphany of agape love accessed within a transcendent horizon. Frame of reference is very important here. In fact, he never refers to this central theme in the Christian New Testament in his analysis of technologies of self. His focus is on the restrictive, self-negating versions of Christian self-construction, which calculate as good reason to deconstruct, reject and move beyond its ethics. This is a tragic miscalculation in the sources of the self and identity.

At this juncture in my discussion of a transcendent turn, it is valuable to move beyond the philosophical insights of Charles Taylor. I want to enlist the aid of two key theologians, D. Stephen Long and Christof Schwöbel, for a richer articulation of the point of a transcendent turn to the divine good/goodness. Their work on the interface between divine and human goodness shows strong resonance with Taylor’s trajectory of such a turn to agape love. Taylor also follows this argument through into his book A Secular Age. The following discussion will help to define more fully the rich and creative character of such transcendence and the concept of an epiphanic encounter. In Taylor’s thought, agape, at one level, is a quality of human relationships, a hypergood that informs and even organizes the other goods within one’s horizon. But at another level, agape can also be seen as animating and empowering the ethical subject, and thus reveals a constitutive good which is rooted in transcendent divine goodness. Now let us proceed to a further understanding of this concept and its implications for the moral self.

There is a certain strangeness to the idea of transcendent divine goodness. It exceeds one’s human cognitive grasp, or ability to define it. One can use terms like infinite, excellent, most intense, purest, unfathomable, or superlative as adjectives to describe this goodness. But one cannot fully grasp the qualitative dimensions of transcendent divine goodness with propositions alone. It is radically other, a radical alterity, trans-historical even though it is revealed in time, space, and history. At one level, it is incompatible, incommensurable with human concepts of the good. It is certainly no mere human projection into the cosmos. Goodness that we find in the world points to and participates in, but is not identical with, the goodness that is God.

By definition, it is much more than an absolute or highest principle. Goodness is of the very essence of God and the claim that God is good entails a distinctive character trait. D.S. Long (2001, 21) attempts such an articulation when he writes, “God is good in the most excellent way.” This means that there is no greater good, nor a position of goodness from which to judge God. This is a qualitative transcendence that is worthy of love and admiration, a goodness that is much more than moral virtue or useful goodness. God is the gold standard by which all human currencies of the good are measured. Another way of saying this is that there is an “irreducible density to God’s goodness” (Hardy, 2001, 75). Schwöbel (1992, 72) proceeds logically from this to say that in creation, “God has set the conditions for being and doing the good and for knowledge of the good in the human condition.” On this account, transcendent divine goodness is the ontological/metaphysical ground of the human good. The entire human moral horizon derives from, is rooted in God or contextualized by God. It is not autonomous.

Furthermore, the knowledge of the good is intimately linked with the knowledge of God, and one’s relation to the good is ultimately connected to one’s relationship to God. Long adds the following.

Participation in God is necessary for the good and for freedom. Evil arises when freedom is lost through turning towards one’s own autonomous resources for ethics. The fall does not result from people seeking to be more than they are capable of through pride but from their becoming less than they could be because they separate the knowledge of the good from its true end, God, and find themselves self-sufficient.… Seeking the good through non-participation in God, through the ‘virtue of what was in themselves’ makes disobedience possible. (D. S. Long, 2001, 128)

This important concept is what Long refers to as the blasphemy of the a priori, that is, the philosophical preoccupation that assumes one can determine the conditions for knowledge of the good a priori, without engaging the good at its best in God. This is a working assumption in Foucault’s moral self-making and in so many who follow in his steps. If the individual is the origin of the moral life, ethics would tend to be reduced to anthropology (what a tribe does) or autobiography (what I decide for myself). That is quite a reductionistic stance.

Another conclusion that can be drawn from the premise of transcendent goodness is that this goodness is beyond human control and manipulation, manufacture or manipulation. In the human world it is no mere social, legal or governmental construction of the good. Human attempts to articulate the good, construct the good, or to be good, are only vague, finite and inadequate facsimiles of God’s goodness. These articulations are also vulnerable to manipulation and exploitation, conflict of interpretations, and power interest, as Foucault saw so clearly. Thus people become dismayed and cynical about the very idea of the good or claims to commitment to the good. Some human standards are historically contingent, or a product of self-interest by those in power, employed in coercive or abusive ways, or employed arbitrarily by the leadership. Human claims and social constructions of the good are necessary, but not final. They are accountable to a higher (transcendent) standard. Humans needs a transcendent divine goodness to arbitrate and critique their various human claims to the good, arbitrate between human social constructions of the good.

In the next post, I will show that there is a trinitarian aspect of divine goodness. I also discuss this at more length in chapter five of my book, Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture. This transcendent goodness is relational, a personal goodness of a tri-personal God. This transcendent goodness begins in God and then flows to creation as gift. This transcendence automatically has a relationship to the immanent human world as we see in the incarnation of Jesus Christ. It is communicable, but the understanding and experience of goodness involves a humble journey towards the triune God. At the same time, it involves a revealing of this goodness in the world by God: Moses, Elijah, John the Baptist.

Application: How Does this Help with Current Moral-Spiritual-Identity Crisis Indicators?

I am feeling morally ambivalent; it is hard adjusting from campus hedonism to a responsible lifestyle in society. This can be a form of reckoning.

I am restless with the present employer: It is tough to adapt to an impersonal corporate culture with its never ending demands. Will I be replaced by Deepseek RI or some other form of AI?

I am afraid of marital commitment: There is so much that could go wrong–adulting is hard work with many uncertainties.

I am a bit ashamed about returning to live with my parents: The cost of housing combined with my accumulated student debt is formidable. The economic cards seem stacked against my generation.

I am suffering from the numbing syndrome of narcissism, cancel culture, and emotional turmoil on social media. It really is an addiction as powerful as crack cocaine as Jerone Lanier says.

I cannot help myself; I am constantly in search of the new, the more exciting, of the best ways to be outstanding, original, unique. It is exhausting. When do I arrive somewhere satisfying?

I feel valued only for my productive capacity and efficiency, not as a human being with worth. Matthew Crawford is right about our loss of ethics or broader human values in the workplace—I see all around me workaholism, performance-enhancement drug abuse.

Psychological wellbeing is the only way my generation understands human flourishing: Therefore, any challenge to our mental health is taken as a personal attack–> “You are trying to erase me.”

My generation is cut off from traditional sources of meaning-making (Carl R. Trueman, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self). Expressive individualism that dominates today tends to fragment key relationships—it leads us to become more sociopathic.

Dr. Gordon E. Carkner, PhD, Meta-Educator with UBC postgraduate students and faculty, Author, Blogger, YouTube Webinars and Scholarly Lectures on Christianity and Culture.

Hardy, D.W. (2001). Finding the Church: The dynamic of Anglicanism. London: SCM Press.

Long, D.S. (2001). The Goodness of God. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press.

Schwöbel, C. (1992). God’s Goodness and Human Morality. In C. Schwöbel, God: Action and revelation (pp. 63-82). Kampen, Holland: Pharos.

Schwöbel, C. (1995). Imago Libertatis: Human and Divine Freedom. In C. Gunton (Ed.) God & Freedom: Essays in historical and systematic theology (pp. 57-81). Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

Taylor, C. (2007). A Secular Age, Harvard University Press.

Gordon will give a live workshop at Apologetics Canada’s 2025 Conference in Abbotsford, BC on March 8. https://apologeticscanada.com/conference25-bc/

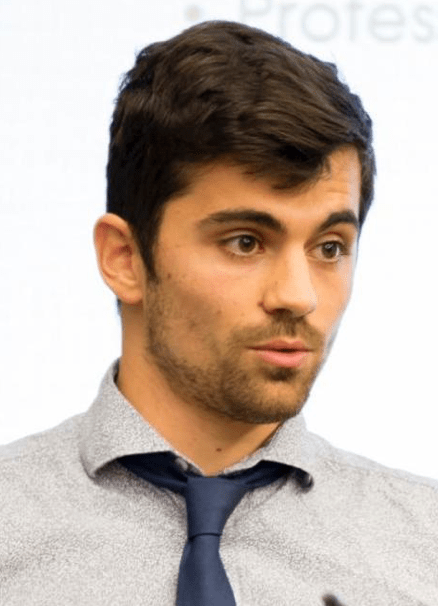

Physician Ethicist Providence Health Care

Emergency Physician St. Paul’s Hospital

Rethinking Medical Ethics in Light of the Good

Tuesday, March 4 @ 12:00 PM

UBC GFCF is inviting you to its March 4 Zoom Lecture.

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us06web.zoom.us/j/88565585788?pwd=TfS3VRkeFlIojQe9ovKSo3yuEFA431.1

Abstract

What features define human life and the value of the individual? How do individuals and communities understand and withstand suffering and pain? What is good dying? In our time, the essential human questions are often viewed primarily as bioethics issues. In reality, these are not exclusively medical or bioethical inquiries. Rather they are complicated and challenging ethical questions with which all human beings and societies must grapple. How does Christian philosophy and theology inform these life and death questions at deeper, more foundational levels?

Biography

Dr. Quentin Genuis MD is an Emergency Physician at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, and the Physician Ethicist for Providence Health Care. He holds a Master of Letters in Ethics from the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. He teaches in academic, clinical, professional, and lay settings on a variety of issues related to bioethics. His research and writing interests include the autonomy debates, end-of-life care, compassion, human dignity, addictions, and theological anthropology.

See also the new Routledge Handbook on Christianity & Culture https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Handbook-of-Christianity-and-Culture/Ariel-Thuswaldner-Zimmermann/p/book/9780367202590?srsltid=AfmBOorfmXlbleBFgf-1MEVzQZexWKc4aLFSfTZ-EFWGefDA46d0zsTW

Leave a comment