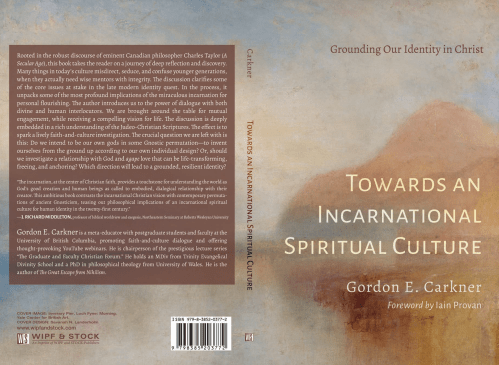

My Newest Book Now Available on Amazon & at Bookstores

Dear Friends,

Special Offer from Wipf & Stock

There is a unique opportunity while it lasts to access the Kindle version of my book, Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture, for FREE ($0 cost). You can buy a copy on Amazon.

Let me know if you have any questions,

Gord Carkner gord.carkner@gmail.com

Dr. Gordon E. Carkner

Reviews: https://bobonbooks.com/2024/08/12/review-towards-an-incarnational-spiritual-culture/

The Book’s Genre (non-fiction): Finding God at Harvard by Kelly Monroe Kullberg; The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self by Carl R. Trueman; Surprised by Oxford by Carolyn Weber; On Human Nature by Roger Scrutin; The Genesis of Gender by Abigail Favale; Culture Making by Andy Crouch; Faith and Wisdom in Science by Tom McLeish; Incarnational Humanism by Jens Zimmermann; and You Are What You Love by James K. A. Smith. Like Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony Pastorale, the book entails five movements in five chapters.

Contents

Foreword by Iain Provan | ix

Acknowledgments | xi

Introduction | xiii

1 Comparing Gnosticism to an Incarnational Stance | 1

2 God’s Grand Invitation to Dialogue: Where Are You Speaking From? | 12

3 Jesus the Ground of Wisdom | 30

4 Incarnation: Individuals Engaged in Community | 54

5 Transcendent Goodness Meets the Good Society | 81

Conclusion | 110

Addendum: What Do People Mean by a Personal Relationship with Jesus? | 115

Bibliography | 121

More Scholarship on Incarnation & Social Implications:

See David P. Gushee & Glenn Stassen, Kingdom Ethics: Following Jesus in Contemporary Context, 2nd Edition, Eerdmans, 2016. Great followup to Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture.

See also: pages 223-303 of Circles and the Cross: Cosmos, Consciousness, Christ, and the Human Place in Creation. Cascade Books, 2023, written by Dr. Loren Wilkinson, Professor Emeritus Regent College (his magnum opus). Brilliant: very informative on science, religion, and human culture.

Quote from Chapter 3.

The New Testament makes the amazing claims that Jesus is, in the flesh, the wisdom of God and the power of God (1 Cor 1:24). He is the nexus of knowledge and ethics, integral to the relationship between faith and reason. As the divine Logos (John 1:1–4), he is the transcendent Word made flesh, plus the underwriter of all human thought and language. Truth ultimately is found embodied in a person of highest credibility, not a mere philosophy or ideology. Jesus is deep reason personified, the raison d’être of it all. The narrative is clear: The incarnation is a communicative action, a theodrama, not just letters, propositions, or sentences. The Jesus story is wisdom writ large, saturated with insight that offers a foundation for addressing our past, present, and future. Can the incarnation form the basis for reconciliation, confront lies and violence, bring peace and heal divisions? As we proceed, we long to explore the depths of this question. Christians believe that all truth points to its source in Christ, the Creator of all things in the cosmos. We arrive at the truth when our thoughts, beliefs and statements correspond to reality, when we are properly related to the world as it is— known as critical realism. Therefore, faithfulness to Christ requires diligent cultivation of the intellectual virtues.

Christians ought not to be anti-intellectual, because the pursuit of knowledge is valuable in its own right. It reveals more about God and the wonder and complexity of his world. I have enjoyed many great mentors who have brought me closer to a more disciplined understanding of the truth. They inspired me with a hunger for acute knowledge and cogent insight. Our faith and beliefs should not be based on myth, scam, or hearsay, but critical biblical, scientific, and historical thinking. We are more secure in our beliefs when they have been tested as in our debates with culture (1 Pet 3:15). I have always been a strong advocate of honest and robust Christian apologetics and engaging dialogue in my campus career. Among my favorite thought leaders are: Norman Geisler, Alvin Plantinga, James Sire, William Lane Craig, Brian Walsh, C. Steven Evans, Rebecca McLaughlin, James K. A. Smith, and Charles Taylor. This is important because our beliefs matter deeply—they are the very rails on which our life travels. In biblical theism, mind is prior to (transcends and causes) matter or body. Philosopher Paul Gould speaks to the logic of hard thinking and rigorous investigation.

“We would expect a perfectly rational and good personal being to spread his joy and delight by creating a world full of epistemic, moral, and aesthetic value. For in such a world it is possible to love, know, act, and create. It is easy to see how such features could be exhibited in a world created by a personal God.”

Gould captures the fuller breadth of Christian reflection (science, ethics, the arts) answering the tough questions put to the Christian faith. It makes a vast difference if we are in a world governed by truth and not mere survival instincts or rebellion against all tradition.

Key Interlocutors in the Book: Hans Urs von Balthasar, Charles Taylor, Michel Foucault, James Davison Hunter, Calvin Schrag. See new blog series on Charles Taylor’s Wisdom at: https://ubcgcu.org/2024/05/17/charles-taylors-wisdom/

Education: The book makes a great companion volume to Christopher Watkin’s tome on faith and culture, Biblical Critical Theory; or Carl R. Trueman’s The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self; or Jens Zimmermann, Incarnational Humanism, for the classroom.

Radcliffe Camera Bodleian Library, Oxford University

Gordon’s Delightful Research Resource for Several Years

You can find Gordon Carkner’s doctoral dissertation in the Bodleian Library, Regent College Library or request the pdf version from gord.carkner@gmail.com. John Webster was his first reader; Donn Welton his second.

“A Critical Examination of Michel Foucault’s Concept of Moral Self-Constitution in Dialogue with Charles Taylor”

The Author Dr. Gordon E. Carkner is a meta-educator with postgraduate students and faculty at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada: promoting faith and culture dialogue, blogging, and offering thought-provoking YouTube webinars. He is chairperson of the Distinguished Scholar lecture series UBC Graduate and Faculty Christian Forum (https://ubcgfcf.com) that has run for some 35 years. He holds a Bachelor of Life Science in Human Physiology from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario; a Master of Divinity from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, and a PhD in philosophical theology from University of Wales. He has also read extensively on the subject of science and theology at Regent College. He is the author of The Great Escape from Nihilism: Rediscovering Our Passion in Late Modernity; and Mapping the Future: Arenas of Discipleship and Spiritual Formation. He also hosts a blog (https://ubcgcu.org) and a YouTube video channel(https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCl4NgIg_ht8IZCRIhho4nxA) which contain many resources and creative conversations. Carkner works out and loves to hike and bike with his wife and friends. Early in their relationship, Gordon and Ute spent seven days hiking the Grand Canyon with a wilderness group. The couple love to host many different hospitality events with students, faculty, and friends in their home and on campus. They attend Westside Church in downtown Vancouver, Canada. Gordon participated in the first European Conference of IFES which brought together students from Eastern and Western Europe just after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Dr. Gordon E. Carkner, Author of Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture

“I hope you are inspired to think, dream and live better through entering this amazing discourse of incarnational life and spirituality.”

Production Status: The Book has Launched! It is available for purchase from Wipf & Stock Publishers from Amazon, E Bay, Goodreads, Indigo, and Regent College Bookstore. Write to Wipf & Stock for best price on bulk purchases: orders@wipfandstock.com

Christian College & Seminary Deans are recommending the book to their faculty for a classroom text.

Devotional on Incarnation: https://www.royalperspectives.com/a-prayer-of-thanksgiving-for-the-incarnation-based-on-1-john-11-4/

Topics Discussed in the Book Assumptions of Gnosticism, Essentials of Dialogue with God, Christian Anthropology and the Image of God, the Sheer Grandeur of the Incarnation, the Ultimate Ground of Human Wisdom, Faithful Presence as a Wise Incarnational Stance, Wisdom of Servant Leadership, Recovery of the Moral Good, Debate between Expressive Individualism and Community-Mindedness for Healthy Identities, the Narrative Self as Balance to Cultural Extremes in the Quest for Identity, Physics of the Self and the Spirituality of Bodies, Language and Identity Hermeneutics, Transcendent Goodness Meets the Good Society, Agape Love as a Whole New Set of Power Relations, Jesus Shows up as Incarnate Goodness, the Holy Spirit as Conduit and Translator of Transcendent Goodness, Incarnational Spirituality as a Countercultural Stance in Late Modernity. Overall, it engages: Philosophy, Religion, Social Imaginary, Atheism, Humanity, Responsible Freedom, Love over Power as a Prime Motive.

Logos: We live in a word-based universe. We are familiar with the significance of mathematics for scientists to understand the physical universe. We have recently had a breakthrough in biology, the full human genome–the longest word/code in the world. The bigger question is “What are the implications that God has encoded himself in a human being, Jesus of Nazareth as Christ, as Logos?” It requires deep humility to see this in the fullest, richest sense (John 1:1-5).

What’s Unique About this Book?

It raises the bar on what we should expect of God and what he expects from us. It leads to a faith experience that is both more challenging and more rewarding. The James Webb Telescope is an example of what we humans can accomplish when we come together for the sake of the good, to seek out good reason, insight, knowledge, and wisdom.

It penetrates the mythology of late modern culture in a language that is accessible to the non-theologian and non-philosopher, while walking the tightrope of philosophical and theological accuracy/astuteness/cogency. Incarnational theism offers an engaging hermeneutic of culture.

It alerts us to the minefields that are hidden along the roadway of contemporary cultural discourse and debate. Our very identity and hope for the future is at stake.

It explores the great reversal narrative for those stuck in life or career. Once we see the big picture of Jesus the Christ (especially in chapter 3), it will amaze, lead us to humility and empower within us a fresh imagination.

It emphasizes the interwovenness of identity, ethics, personal narrative, and spirituality. It reconnects our quest for freedom with responsibility for self and others—towards compassion, hospitality, servant leadership, and constructive citizenship.

The practice of incarnational spirituality and faithful presence heals families, humanizes business, improves education, promotes creative politics, and good healthcare. It offers a trajectory that empowers life, promotes justice and mercy. See William T. Cavanaugh, The Uses of Idolatry (OUP, 2024)

Mercy and Justice: It encourages both seekers and Christian believers alike to reflect more deeply on the meaning and purpose of life, on one’s calling in life and one’s potential for positive impact, and to find the motivation to live the renewed, reinvigorated life.

The discussion helps us zoom out and zoom in with respect to our late modern culture for the purpose of acute discernment on contentious issues like identity. It offers discovery of a platform for hope, ideas for fruitful engagement. It confronts cultural ideologies that handicap us, push us down, and block our progress as a species.

Foreward by Iain Provan

We live in a world marked by crises of various kinds, but perhaps most deeply and fundamentally by a crisis as to the nature of our humanity. What does it mean to be human?

For example, are human beings essentially minds, trapped temporarily and regrettably in physical bodies? Certainly many artificial intelligence enthusiasts see the world in precisely this way. Marvin Minsky, for example, believes that the mind is all that is really important about life, over against that bloody mess of organic matter that is the body. Out of this conviction arises another: that mind machines represent the next step in human evolution. We ourselves, in our god-like state, ought to create this new species—Machina sapiens instead of Homo sapiens—passing the torch of life and intelligence on to the computer (Rudy Rucker). Our ultimate goal is the conversion of “the entire universe into an extended thinking entity … an eternity of pure cerebration” (Hans Moravec).

From this single example we gather what should already be obvious to us in any case: that our governing ideas about human nature inevitably have significant consequences. They matter individually, affecting how I look at myself, what I agree to do to myself or have done to me, and the goals I set myself. They also matter communally, affecting how I look at and treat other people, and what kind of society I am trying to help to build. In fact, the answer to this question about humanness affects everything else that matters in life. And this means that arriving at good rather than bad answers to the question is a high-stakes game. It means that arriving at the truth of the matter is crucially important. Is it really true, for example, that we are essentially minds that happen to possess bodies that we may or may not consider satisfactory? If we can manage it, should the physical body be discarded like a piece of clothing in pursuit of something more glorious, with the help of technology?

It is into the very centre of this kind of contemporary discourse that Gordon Carkner has inserted this new book about incarnational spiritual culture, with a view to encouraging readers to ground their identity in Christ, rather than somewhere else. He invites us to consider the great difference between incarnational spiritual culture, on the one hand, and both ancient and modern anti-material Gnosticisms, on the other – rejecting the latter in favor of the former. He explores the Incarnation of Christ as the centre-point of history, giving dignity to embodied persons everywhere, and enabling us to rethink human wisdom and knowledge. He pursues the implications of this Incarnation for human community and communion, contrasting the contemporary will-to-uniqueness, that tears us apart, to the will-to-community, that re-integrates us. And he discusses, finally, the transformative nature of divine goodness, and its necessity for healthy human freedom.

We need all the help we can get in remaining human in these markedly inhumane times. This volume draws on deep and varied resources in offering such help, and I know that many people will benefit from reading it.

Dr. Iain Provan, Founder of the Cuckoos Consultancy, Author of Cuckoos in our Nest: Truth and Lies about Being Human; former Professor of Old Testament, Regent College

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tS7s9kDPKNw The God of All Comfort by St. Andrew’s University Professor N. T. Wright from Isaiah 40. This sermon provides a great onramp into the Advent and Christmas Season.

The Gospel & the Incarnation from Dr. Jeremy Begbie, Theology Professor, Duke University

The veracity of the gospel–the claim that, in Christ, God has decisively reconciled humans to God–hinges on Christ being fully human, subject to the conditions of bodily life where people and things are related to one another in a way appropriate to the spatiality of the created world. But the gospel also hinges on the Son being at every point the eternal Son of the Father, sharing the Father’s being and life, living as the one through whom all creation is upheld and held together. That is to say, the incarnate Son inhabits both the “space” of the triune God (primordially) and the space of the world. God’s immensity, God’s uncontaianbility by created space–therefore has nothing to do with the impossibility of fitting God’s enormity into a finite container. It has everything to do with the pressure of divine love–with God’s desire to relate creatively and savingly to the entirety of the world as spatial, and yet without that spatiality being compromised in any way. John Webster writes: Immensity and embodiment … are not competing and mutually contradictory accounts of the identity of the Son of God. Incarnation is not confinement, but the free relation of the Word to his creation–the Word who as creator and incarnate reconciler is deus immensus.” (Jeremy Begbie, Abundantly More, 2023, 141-2)

Meaning: As Jesus the divine Son grew in Mary’s belly, he was also upholding the universe.

Incarnation Improves our Humanity

In Christian theology, Jesus reveals to us not only who God is but also what it means to be truly human. This true humanity is not something we achieve on our own; it comes to us as a gift. . . . The reception of this gift contains an ineliminable element of mystery that will always require faith. Jesus in his life, teaching, death and resurrection and ongoing presence in the church and through the Holy Spirit . . . orders us towards God. He directs our passions and desires towards that which can finally fulfill them and bring us happiness. (D. Steven Long, The Goodness of God, 106-7)

Quote from Chapter 4. Incarnational Community

We begin this chapter with some appropriate philosophical reflection together with Dr. Calvin Schrag in order to build on the previous discussion: “Community is constitutive of selfhood. It fleshes out the portrait of the self by engendering a shift of focus from the self as present to itself to the self as present to, for and with the other.” Many philosophers in late modernity lack a sense of the “we-experience” or the phenomenon of being-with-others. Michel Foucault, for example, is focused on freedom, aesthetics, and the art of self-care as a major goal, assuming individuals ought to produce an identity separate from community—something unique, even rebellious or revolutionary. Life for Foucault is about prying oneself loose from community obligations. This sentiment can easily be found in many other radically individualist late modern philosophers. The rhetoric of communal action, however, has an important role today: the idea of discovering and constituting oneself in fruitful relationship to others. This was one of the key themes to discern during my doctoral work. My own conclusions resonated with those of Professor Schrag. This is the same self that constitutes itself through discourse or narrative and embodied action.

Community is more like a binding textuality of our discourse and the integrating purpose of our action. . . Community, reminiscent of the ancient Greek concept of the polis, takes on a determination of value and is indicative of an ethico-moral dimension of human life. Self-understanding entails an understanding of oneself as a citizen of a polis, a player in an ongoing tradition of beliefs and commitments, a participant in an expanding range of institutions and traditions. Community is not a value-free description of a social state of affairs. The very notion of a communal being-with-others is linked to normativity and evaluative signifiers. . . . The discourse that is operative in the process of self-formation is a mixed discourse, in which the descriptive and the prescriptive, the denotative and evaluative, commingle and become entwined. . . . The “sociality” of being with is always already oriented either towards a creative and life-affirming intersubjectivity or towards a destructive and life-negating mode of being-with-others. (Calvin Schrag, The Self After Postmodernity, 86-88)

Endorsements of the Book

The incarnation, at the center of Christian faith, provides a touchstone for understanding the world as God’s good creation and human beings as called to embodied, dialogical relationship with their creator. This ambitious book contrasts the incarnational Christian vision with contemporary permutations of ancient Gnosticism, teasing out philosophical implications of an incarnational spiritual culture for human identity in the twenty-first century.

J. Richard Middleton, PhD, Professor of Biblical Worldview and Exegesis, Northeastern Seminary at Roberts Wesleyan University

In his new book, Gordon Carkner surveys a wealth of philosophical literature and shares much of his own practical wisdom. The book shows clearly how strongly influenced our society is by modern versions of Gnosticism and how diametrically opposed that is to the biblical teaching of an incarnational life, practised first by God himself in Christ and then by his followers. Reading the book as a computer scientist doing research in the area of AI, it occurred to me that Gnosticism also seems to be the root of the misunderstanding in the AI community that reduces humanity to intelligence, to the fulfilling of functions, as evaluated for example by the Turing Test. Last but not least, I know from various experiences of Gordon’s hospitality that he indeed practices an incarnational lifestyle. It is a great book on a very timely topic which should be of interest to Christians and sceptics alike.

Dr. Martin Ester, Distinguished Professor of Computer Science, Simon Fraser University

It’s easy to see that we are in the grip of a cultural identity crisis! What’s not so easy to see is a way out. Dr. Carkner provides both the head and heart knowledge necessary to ground our identity in Christ in such a way that leads to the flourishing of ourselves and our communities. I highly recommend this thoughtful and passionate engagement with today’s most pressing challenge – our identity.

Andy Steiger, PhD, founder and president of Apologetics Canada and author of Reclaimed: How Jesus Restores Our Humanity in a Dehumanized World.

This reflective work by Gordon Carkner comes to us at a poignant moment. More than ever, people need to grapple with the grandeur, beauty, and coherence of the incarnation—the Jesus story. At its core, it is a transformative, reversal narrative, where prodigals and cynics are invited to become compassionate healing agents, committed to justice and mercy. This book offers a tremendous resource for pastors and church members who want to live out dramatically the artfulness of agape love.

Matthew Menzel, Lead Pastor, Centre Church, Vancouver, B.C.

Having read widely and deeply in contemporary literature and philosophical thought, Gordon Carkner is able to alert us to the ‘minefields’ hidden along the highway of contemporary culture, especially contemporary Western culture. But this is not only a critique of that culture. Being deeply rooted in the Judeo-Christian faith, Carkner is also able to guide us to vistas of great grandeur embedded in the biblical account of creation and re-creation.

Sven Soderlund, Professor Emeritus of Biblical Studies, Regent College

Gordon Carkner’s latest book is an important work of theological anthropology examining the grounds for human dignity through the lens of the incarnation of Christ. Carkner dialogues with thinkers such as Charles Taylor who increase our articulate grasp of the issues and broaden our understanding of the incarnation as the epicenter for a thick identity, grounded in God and nurtured by grace. Such an identity prepares us for a robust engagement with, and critique of, late modern culture.

Dr. Andrew Lawe, MD, FRCS(C), General Surgeon and Clinical Instructor, UBC Southern Medical Program

This book develops a profound idea: that in the incarnation, God’s glory and generosity have been revealed in Jesus as publicly accessible truth. Furthermore, the God who was incarnated invites us to try life with him. Be prepared for a provocative journey through several contemporary ideologies elucidated by the insights of philosopher Charles Taylor and other important thinkers. It may result in a deeper appreciation of the presence of the glorious creator whose signs of transcendence surround us.

Paul Chamberlain Ph.D., Professor, Ethics & Leadership, Trinity Western University, Langley, B.C., Canada.

Edwin Muir The Incarnate One

The windless northern surge, the sea-gull’s scream,

And Calvin’s kirk crowning the barren brae.

I think of Giotto the Tuscan shepherd’s dream,

Christ, man and creature in their inner day.

How could our race betray

The Image, and the Incarnate One unmake

Who chose this form and fashion for our sake?

The Word made flesh here is made word again

A word made word in flourish and arrogant crook.

See there King Calvin with his iron pen,

And God three angry letters in a book,

And there the logical hook

On which the Mystery is impaled and bent

Into an ideological argument.

There’s better gospel in man’s natural tongue,

And truer sight was theirs outside the Law

Who saw the far side of the Cross among

The archaic peoples in their ancient awe,

In ignorant wonder saw

The wooden cross-tree on the bare hillside,

Not knowing that there a God suffered and died.

The fleshless word, growing, will bring us down,

Pagan and Christian man alike will fall,

The auguries say, the white and black and brown,

The merry and the sad, theorist, lover, all

Invisibly will fall:

Abstract calamity, save for those who can

Build their cold empire on the abstract man.

A soft breeze stirs and all my thoughts are blown

Far out to sea and lost. Yet I know well

The bloodless word will battle for its own

Invisibility in brain and nerve and cell.

The generations tell

Their personal tale: the One has far to go

Past the mirages and the murdering snow.

Qualities of a Strong Identity for Philosopher Charles Taylor Humans at their best, their fullest, richest linguistic and social capacity

- Their words and actions cohere-integrity.

- They pursue what is of top significance without deviation. They pursue wholeness and unity of motives, not confusion, brokenness, and fragmentation.

- They overcome dispersal, contradiction, or self-stifling: temptations to reduce themselves to something less or lower (the race to the bottom).

- The results of this pursuit involve us in seeing better, believing better, loving better, and living a more wholistic life. We respect our future self by taking our present self more seriously through more responsible behaviour. Never forget that we are always situated in moral space, on a moral journey, we are a thoroughly moral creature. Morality is intimately entwined with identity, narrative, community, and spirituality.

The Logic of Incarnation—Why God Took on Human Flesh Incarnation concerns both the Person and the Work of Christ…. Incarnation impacts salvation, theological anthropology, and the doctrine of God. It is about much more than mere remedy or repair. Christ is complete and characteristically distinct in his humanity. The divine Word does not change or evolve, but takes humanity up into divinity. Incarnation is grounded in the nature of God, even as it creates a whole new and profound relationship with humanity, and offers a gift to raise the dignity of human beings. The Word is eternally part of Jesus the man—who is both human and divine. But the incarnation does not exhaust God of his plenitude. Like creation, it does not change or restrict the Creator. It rather shows the love and artfulness of God in a human mode, divine holiness in the course of a human biography, revealing the infinite God in finite ways, in a finite, time-space world. Jesus most fully bears the Image of God, restoring it from its longterm corruption—an act of solidarity and redemption intended to restore key human capacities to know and to love (relationally, reflectively, with receptivity and agency), to do justice and love mercy. There is a deep coherence and beauty to all the dynamics of incarnation. All that prepares for it and follows from it, is a drama into which human life, history, and culture is gradually drawn. Above all, Christian theologians would want to say that the incarnation, even more than the presence of human life, crowns the extraordinary dignity of life on earth, or the dignity of the entire cosmos. ~Andrew P. Davison, Professor of Theology and Natural Science, Cambridge University (now moved to Oxford). He is author of Astrobiology and Christian Doctrine: Exploring the Implications of Life in the Universe.

Six Pillars of Incarnational Wisdom (in Chapter 3.)

- Positive Revelation.

- Existential Hermeneutic.

- Transcendence and Immanence.

- Entails a Sense of Wonder.

- Orthodoxy Combines with Orthopraxis and Orthopathos

- Church Social Practice and Agape Miracles.

The Incarnation opens the possibility of seeing the invisible without reducing the invisible to the visible. God’s transcendence does not mean God is far away. As creator of all, God is wholly other to creation, and precisely therefore God is not another thing competing for space with created things. As the ground of all being, God is innermost to all beings. God is both wholly transcendent and wholly immanent in all things. One does not have to leave the world behind to experience transcendence. (William T. Cavanaugh, The Uses of Idolatry, 361)

Christ is the one in whom and for whom all is created, and Christ is the ultimate destiny of the world. (Col. 1:15)

Those who make gods become less than earthly raw materials by trying to fashion themselves into gods, while those who allow earthly materials to be signs of God who made them become assimilated to the divine life…. Human-made images mire humans in creation; God-made images elevate humans to participation in the Creator. For Augustine, sacramental signs are not mere products of human creation but participate in the Incarnation, in which God takes on material creation. The most important God-made images of God, however, are human beings themselves. When they live as they are called to live in charity, they reflect God rather than see their own reflection in the images they create. (William T. Cavanaugh, Ibid., 189)

Summary of Augustine’s Contribution: For Augustine, the worship of other gods is a manifestation of a broader turning away from God and toward creation. Creation can be read iconically as a window to the divine, but it can also be read as a mirror that narcissistically reflects our own wants and pleasures and fears back to us. The ethical consequences of such idolatry can be dire, including violence against the other for being other, and neglect of the needs of the other for falling beyond the purview of our own desires. Healing idolatry necessitates overcoming the dichotomy of self and other and participating in the circulation of love that includes oneself, one’s neighbour, and God. (William T. Cavanaugh, Ibid., 189)

Following an invisible God is hard; it exhausts the human capacity to be patient and to live with uncertainty and a lack of signs that appeal to our material nature. Jesus is claimed to be the very image of the invisible God (Col 1:15; 2 Cor 4:4). Jesus is a living person who manifests the being of God. The Incarnation… is a statement about how God has chosen to use material reality to reveal Godself, not a statement about the intrinsic revelatory nature of material reality as such. Christianity moves from God to humanity, while idolatry moves from humanity towards the divine (attempting to grasp/manipulate the divine). The image of God restored in humanity by Jesus Christ is a gift of God, not a ladder which we can climb to attain God. (W. T. Cavanaugh, Ibid., 141)

Central to the Incarnation is a profound sense of communion, both with our contemporaries and with those who have gone before us. Quoting Charles Taylor, Cavanaugh suggests that “the Incarnation reveals something true about the world and makes possible a different way of living in the world. The Incarnation opens possibilities not just for Christians but for the world more generally.” (W.T. Cavanaugh, Ibid. 346)

We too are also icons of Christ as he is an icon of the Father: “Rather than render gods in the image of humans, God renders humans in the image of God by restoring that image through Jesus Christ.” (W.T. Cavanaugh, Ibid. 347)

God is the one who commits to this creation, who sees it through, who is creation’s eschatological consummator…. We exist in order to be friends of the incarnate God. Sin is best understood as resistance to being with God, our preference to be gods instead. The Incarnation invites us to see God’s elective act of self-giving in all of creation. This is about how God wants to be with us, the action of God’s self-gift. The incarnation opens the possibility of seeing the invisible God. (W.T. Cavanaugh, Ibid. 355, 57)

In Christ we encounter God who undoes idolatry by offering healing for our relationships with God, with each other, and with the material world. Christ is God coming as a gift, descending to defuse the desire to climb to the place of God. (W. T. Cavanaugh, Ibid. 358)

The beauty of creation is not sufficient in itself to lead us to God because of sin and our ambivalence to such beauty. “The Incarnation is necessary because Christ, as begotten, not made, is able to reveal the nature of divine Form; Christ is the very image of the invisible God (Col. 1:15), but in a manner that humans can fathom. Christ is the Incarnation of supreme Form or Beauty. What we love in loving Christ, even in his human form, is no created thing but divine Beauty itself, “beauty so old and so new.” (W. T. Cavanaugh, Ibid. 353)

To acknowledge God as God, and therefore to turn from idolatry, is to acknowledge that God is Lord of history, despite human sin. It is because Jesus Christ has somehow saved the world that we are called to and enabled to participate in that salvation, to live sacramental, though imperfect, lives…. We are called to let our lives be conformed to the sacrament of God’s presence in the world. (W.T. Cavanaugh, Ibid. 381)

Circulation, not accumulation, is the point of a gift economy. Abundant life is not defined as possessing more things but as participating in the common good, the circulation of goods to all…. All goods belong to God, are inaugurated by God. What is needed is an economy based in gratuitousness and communion. We are recipients of God’s munificence. The most fulfilled people are those who communicate life to others. Jesus summons us to the revolution of tenderness. Going up against idolatry is fundamentally an act of thanksgiving for all the good gifts that God has lavished upon us, grateful for being loved into being by God. (W.T. Cavanaugh, Ibid. 387)

The community receives its identity not by looking in a mirror narcissistically but by looking toward the weakest among them, who are icons of the self-emptying God whose power is made perfect in weakness (2 Cor 12:9). Paul sees the connection between encountering Christ in the bread and wine and encountering Christ sacramentally in the poor and weakest, the most marginalized among us. This is endemic to the circulation of agape love within the body, towards breaking down barriers. Jesus offers himself as a sacrifice of reconciliation and a new covenant to gather the nations.

Quote from Chris Watkin: The incarnation acts as the pinpoint focus to which all time before it is drawn, and from which all time after it radiates out…. At the incarnation, the narrative that began with the heavens and the earth converges on a single baby as it “sharpens at last into one small bright point like the head of a spear”…. As we move forward in time past the incarnation, we will witness not a further restriction but an explosion in the scope of the narrative as, by the end of the Bible, God’s plans are again seen to encompass the whole universe…. The incarnation is an event that splits time in two…. Of all the biblical events that irreparably alter the course of history and create an indelible “before” and “after,” the incarnation is perhaps the one that has left the deepest mark on modern culture. It gives rise to today’s most widely celebrated Christian festival, Christmas, and the contrasting juxtaposition of almighty deity and fragile newborn has captured the minds of countless artists and poets, as well as the hearts and imaginations of many believers…. “What makes the form of Christ attractive,” writes William Cavanaugh, “is the perfect harmony between finite form and infinite fullness, the particular and the universal.”… Christ bridges Lessing’s ditch with his own universal particularity, forever uniting the immediate and the ultimate, life and reality, experience and truth. (C. Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory, 349-51)

Two Great Alternatives Quote from Chapter 5.

The two great alternatives facing us today are either: a. Promethean arrogance; or b. The great adventure in humble obedience represented so elegantly in Philippians 2. Nietzsche saw the great divide in human culture as between Dionysus and the Crucified. (See René Girard, “Dionysius versus the Crucified.”). Paul shows us in Philippians that we must seek unity and therefore descend before we ascend, humble ourselves before a God (and one another) who exalts us, builds us up through his grace. Love, truth, and obedience are creatively intertwined (John 14:21). Truth and spiritual freedom can only be discovered when obedience to Scripture (taken as God’s will and voice) remains the protocol for action. Former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, writes, “At its centre and permeating its relationships is the conviction that truth can only be shown and spoken in compassion—attention to the other, respect for and delight in the other, and also the willingness to receive loving attention in return.”

Chantal Delsol’s Definition of Evil: The Greek concept of diabolos literally means “he who separates,” he who divides through aversion and hate; he who makes unjust accusations, denigrates, slanders; he who envies, admits his repugnancy. The absolute Evil identified by our contemporaries takes the form of racism, exclusion or totalitarianism. The last in fact appears to be the epitome of separation, since it atomizes societies, functions by means of terror and denouncement, and is determined to destroy human bonds. Apartheid and xenophobia of all varieties are champions of separation.

Chantal Delsol’s Definition of the Good: For contemporary man, the notions of solidarity and fraternity, and the different expressions of harmony between classes, age groups, and peoples, are still associated with goodness. The man of our time is similar to the man of any time insofar as he prefers friendship to hate and indifference, social harmony to internal strife, peace to war, and the united family to the fragmented family. In other words, he seeks relationship, union, agreement, and love, and fears distrust, ostracism, contempt, and the destruction of his fellow men. . . . The good has the face of fellowship, no matter what name it is given, be it love, the god of Aristotle, or the God of the Bible. The certitude of the good finds its guarantee in the attraction it induces. The separation of the diabolos occurs constantly, but one day or another it will be pursued by mortal shame.

The Book’s Trajectory: Rooted in the robust discourse of eminent Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor (A Secular Age), this book takes the reader on a journey of deep reflection and discovery. Many things in today’s culture misdirect, seduce, and confuse younger generations, when they actually need wise mentors with integrity. This journey clarifies some of the core issues at stake in the late modern quest for identity. In the process, it unpacks some of the most profound implications of the miracle of the incarnation for personal flourishing, highlighting its amazing grandeur. The author introduces us to the power of dialogue with both divine and human interlocutors. We are brought around the table for mutual engagement, while receiving a compelling vision for life. The discussion is deeply embedded in a rich understanding of the Judeo-Christian Scriptures. The effect is to spark a lively faith-and-culture investigation. The crucial question we are left with is this: Do we intend to be our own gods in some Gnostic permutation—to invent ourselves from the ground up according to our own individual design? Or, should we investigate a relationship with God and agape love that can be life-transforming, freeing, and anchoring? Which direction will lead to a grounded, resilient identity?

The Urgency, Tension, and Expectancy of Our Moment in History Many people today sense God calling them to rethink life, to pursue something more challenging, noble and meaningful. They sense him calling them to move forward and upward—out of their self-pity, narcissism, and consumerism. They have tired of workaholism, resentment, anxiety, and sullenness. Before his burning bush encounter, Moses was also stuck in an aimless life, in a vocational cul-de-sac. Perhaps we are also called to launch a journey, innovate a solution to a major problem, make a medical breakthrough, stop a war, or follow a life-changing quest. This book is written to inspire young people who have become fearful, disengaged, and alienated to take responsibility for their world as peacemakers, community builders, healers, and servant-leaders. It is a turn-around story with real vision: where former egocentrics, prodigals, and cynics are transformed into constructive people who explore compassion, just treatment of the poor, widows, and orphans. (G. Carkner, Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture)

Quote from the Book on the Miracle of the Incarnation God’s speech in Jesus is embodied, full-blooded, not flat, lifeless or atomistic. Incarnation is a communicative action, so much more than mere letters, words, or sentences. It is robust, loaded with spiritual vitality and meaning, heavily weighted with present and eternal consequences. It rings forth like an Oxford college bell—it is poetic, prophetic, and pedagogical. Incarnation, as a dynamic theodrama, means that God has bound himself with humanity’s very destiny. We are stunned, but at the same time transformed through its contemplation. We urgently need to engage the veracity of incarnational spiritual culture—intellectually grasp it, feel it in our bones, live in solidarity with the miracle. This is crucial in order to avoid Gnosticism on the road to unity, truth, beauty, and goodness, to fulsome, Christ-grounded wisdom and healthy religion. (G. Carkner, Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture)

Profundity of Agape Love Agape is a prophetic love. It refuses to equate anyone with his immediate observable being. A human being is not deeply and essentially the same as the one who is visible to the employer, neighbor, salesman, policeman, judge, friend or spouse. A human being is destined to live in eternity and is fully known only to God. Agape is about the spiritual destiny of the individual; destiny is a spiritual drama. My destiny is my own selfhood given by God, but given not as an established reality, like a rock or a hill, but as a task lying under divine imperative…. Agape is simply the affirmation of this paradox and of this destiny underlying it. Agape looks beyond all marks of fallenness, all traits by which people are judged and ranked, and acknowledges the glory each person—as envisioned in Christian faith—gains from the creative mercy of God. It sets aside the most astute worldly judgment in behalf of destiny (Glenn Tinder, The Political Meaning of Christianity, 25,28).

Quote on Communality The unfathomable goodness and love of God meets humanity through the incarnation, on understandable and practical terms. Jesus Christ addresses each human individually. At the same time, he draws them into a family environment leading to a richer, thick identity. They see and are seen, know and are known, accept and are accepted, experience hospitality and generously share their resources with others. This process of maturity comes to full fruition within dynamic community and creative dialogue, producing a growing experience of communion. Furthermore, the process bestows a substantial dignity and healthy self-worth that makes one more human, more personal, more at home with self in a hostile world. We are not fully ourselves until integrated into community with other humans beings and God, until we actualize this incarnational spiritual culture in our personal life. (G. Carkner, Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Cutlure)

Tom McLeish Speaks about Human Creativity The ability to bring something new and valuable into being is a wonder. At every turn we have found the process of creation to draw on the deepest human energies, most radical thought, and most powerful emotion. Hope, desire, cognition, vision, dreaming, craft, skill, expertise and passion are summoned in the task of conceiving and realizing our imagination. They weave a much more complex picture. (T. McLeish, The Poetry and Music of Science, 301).

Quote on Faithful Presence I have argued that there is a different foundation for reality and thus a different kind of binding commitment symbolized most powerfully in the incarnation. The incarnation represents an alternative way by which word and world come together. It is in the incarnation and the particular way the Word became incarnate in Jesus Christ that we find the only adequate reply to the challenges of dissolution and difference. If, indeed, there is a hope or an imaginable prospect for human flourishing in the contemporary world, it begins when the Word of shalom becomes flesh in us and is enacted through us toward those with whom we live, in the tasks we are given, and in the spheres of influence in which we operate. When the Word of all flourishing—defined by the love of Christ—becomes flesh in us, in our relations with others, within the tasks we are given, and within our spheres of influence—absence gives way to presence, and the word we speak to each other and to the world becomes authentic and trustworthy. This is the heart of the theology of faithful presence (J. D. Hunter,To Change the World, 252).

Who is the Book Written For?

Pastors looking to expand the vision of their teaching and pastoral care, who want to dalogue with a more robust Gospel that engages culture effectively. Medical and legal professionals looking for fresh language of engagement on foundational issues such as freedom, dignity, justice, the body, the beginning of life, the value of a life at any age.

-Parents longing to raise their children into healthy sexual beings amidst cultural gender ambivalence and confusion.

People in their twenties who are looking for a vision to get their lives on a good trajectory–beyond just making a living and learning job skill sets.

Christians who want to broaden their spiritual horizons and grapple with all that God has for them (Philippians 3:12b)–those who want so much more from their faith journey.

People looking for a positive foundation for medical ethics. People who are confused/overwhelmed with the cultural moment that we now inhabit, lawyers interested in the human questions.

Academics and students who love faith and culture dialogue.

Those who are presently struggling with the lack of a sense of calling, purpose, and meaning in their lives.

People who want to explore the higher road of agape love and Christ-grounded wisdom to make a more human world—a nexus between heaven and earth, transcendence and immanence.

Christian colleges and seminaries who want a new resource on faith and culture engagement, Christian anthropology, identity politics. This book works well as a companion volume to the award-winning tome by Christopher Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory; or William Cavanaugh’s The Uses of Idolatry.

A Critical Point: In our globalized world, given the huge military, technological and environmental challenges of our day, the very survival of our species depends on the imperative of a fresh vision of how we can live together wisely, honestly, fairly, and peacefully. We need deep solutions to contemporary problems and threats to human wellbeing.

Eugene Peterson on Why the Material Matters We are not angels. This world that we inhabit is God’s work. Everything we experience, we experience under God’s sky and on God’s earth and sea, in God’s time marked by sun, moon and stars, in the company of the menagerie of dolphins and eagles, lions and lambs, and in the company of image-of-God men and women who come to us as parents and grandparents, children and grandchildren, brothers and sisters, neighbors and relatives, playmates and workmates, students and helpers—and Jesus. Nothing in practice of resurrection takes place apart from stuff to work with—dirt and clay for shaping pots and mugs, stone and timber for constructing homes and churches, nouns and verbs for conveying wisdom and knowledge, cotton and wool for weaving clothes and blankets, semen and eggs for making babies: good works. Work is the generic form for embodying grace. All Christian spirituality is thoroughly incarnational—in Jesus, to be sure, but also in us. (Eugene Peterson, Practice Resurrection, 103)

Gawronski on Jesus as the Word All the fragments of reality, all the words, are drawn to him as metal shavings are to a magnet. He is the primordial Word before all words—the Urwort—who as sharing in the divine essence is also an Überwort, the alpha and omega. . . . In the flesh, he speaks words, fragments themselves which are cast out like a net to gather the original fragments, turned away from their telos by misused human freedom, leading them not to destruction, but to fullness. (Raymond Gawronski, Word and Silence, 188)

Quote on the Importance of our Individual Story In his articulation of moral mapping, eminent Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor looks to narrative depth as a defining feature of the spiritual self, identity and individual agency. Narrative is consequential to the stability and continuity of the spiritual self over time. It comes in the shape of a personal quest, the notion of self as a narrative quest—an idea from philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre. One’s narration of this quest for the good allows one to discover a unity amidst the diversity of goods or noble ideals that demand one’s attention in daily experience. It is especially true of the category hypergood—which helps coordinate and prioritize the various goods in one’s moral life. We speak of agape love as an example of such a hypergood. The healthy continuity of the self through life is a necessary part of a life lived robustly: with integrity, resilience and weight. Taylor along with Paul Ricoeur sees narrative as a key component of the deep structure of self, a temporal depth in his thick concept of the self—one’s historical-moral-spiritual-identity. (G. Carkner, Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture)

Excellent Example of a Life Narrative: Nicholas Wolterstorff, In this World of Wonders: Memoir of a Life of Learning. Eerdmans, 2019.

Supremacy of Christ (Transcendence & Immanence) The Son is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation. For in him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together. And he is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning and the firstborn from among the dead, so that in everything he might have the supremacy. For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross. (Colossians 1:15-20 NIV)

Over the past century or so, as values of duty, collective identity, and conformity have been overtaken by a premium on nonconformity and what philosopher Charles Taylor calls “expressive individualism,” we have been increasingly told that we live our best life when we go our own way, in the face of what “they” tell us to do. And so we obediently obey this ubiquitous social command to be our own master and blaze our own trail.

~Christopher Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory.

Roger Scrutin on Virtue, Freedom and Accountability

Virtue consists in the ability take full responsibility for one’s acts, intentions, and avowals, in the face of all the motives for renouncing or denouncing them. It is the ability to retain and sustain the first-personal centre of one’s life and emotions, in the face of decentering temptations with which we are surrounded and which reflect the fact that we are human beings, with animal fears and appetites, and not transcendental subjects, motivated by reason alone….. Virtues are dispositions that we praise, and their absence is the object of shame…. It is through virtue that our actions and emotions remain centred in the self, and vice means the decentering of action and emotion…. Vice is literally a loss of self-control, and the vicious person is the one on whom we cannot rely in matters of obligation and commitment…. Freedom and accountability are co-extensive in the human agent…. Freedom and community are linked by their very nature, and the truly free being is always taking account of others in order to coordinate his or her presence with theirs…. We need the virtues that transfer our motives from the animal to the personal centre of our being–the virtues that put us in charge of our passions [because] we exist within a tightly woven social context. Human beings find their fulfilment in mutual love and self-giving, but they get to this point via a long path of self-development, in which imitation, obedience and self-control are necessary moments….. Let’s put virtue and good habits back at the centre of personal life.” (R. Scrutin, On Human Nature, 100, 103, 104, 111, 112)

Incarnational Spirituality in Politics: Nihilistic politics tends towards concentration of power, elitism and smugness in our leadership. This results in the polis becoming disenchanted, cynical, overwhelmed by bureaucracy, polarized, tribal, ahistorical. Social media can scramble our brains, increase fear and hate, promote lies and distrust, attack the character of one’s opponent. But politics is not irredeemable, claims CARDUS director Dr. Andrew Bennett, Preston Manning, and TWU Assistant Professor Leanne J. Smythe at a forum on politics in Canada at UBC recently (Houston Centre for Humanity and the Common Good). Jens Zimmermann of Regent College was the host. It is possible to work from the grass roots, take responsibility for your community, respect the village, look into the faces of your constituents. Politics is a gift that should not be abused, and it can be beautiful if we work towards social inclusion and cohesion; we can find solidarity and inspiration around common goods. To do this, we must reconnect with the transcendent, with history, with integrity, and with higher values. We can work towards accountable politicians and responsible citizens who engage the issues in good faith and listen to one another. Politicians can be people with a positive vision for the country and the world. Charles Taylor (Sources of the Self) is a major proponent of the recovery of the language of the moral good in our political and social relationships, promoting personal flourishing, reconciling conflicting interests. Tom Holland (Dominion) argues for the importance of ancient Judeo-Christian values heritage to maintain the spirit of democracy and human rights in the world. Jesus’ political vision is articulated in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7). Another proponent of the common good is Jim Wallis (The (Un)Common Good) who works in Washington towards a moral influence of governance. See also Jens Zimmermann’s book on incarnational spirituality: Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Christian Humanism.

Sittlichkeit is the German word (Hegel) for the concept of the ethical life or ethical order. There is family life, civic society, state laws, community laws, strata laws. Ethical behaviour is grounded in customs and traditions; it is developed through habit and imitation in accord with the objective laws of the community. This is what we call normativity. The question today is whether we are losing this sense of normativity, groundedness, and balance in an age of deconstruction and revolution–late modernity. Our response to the ethos of our age is of highest importance if we want to preserve what is good, wise, true, and beautiful. Listen to Justin Brierly on The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God: https://open.spotify.com/show/7lovL2tXCyAGkbWZM9F9hg?si=PGZddmZZSLyv5REMaLIZ7g

Jesus’s Politics can be a seen as part of “The Great Reversal” (Chris Watkin) seeking out those who were marginalized, and bringing them to the table of compassion and significance:

-those disadvantaged by family circumstance: widows and orphans

-those disadvantaged by geography: strangers, refugees

-those looked down upon because of their occupation or social choices: rebels, prostitutes, and tax collectors

-those marginalized by their physical disabilities: the blind, handicapped, and the lame

-those marginalized by disease: lepers

-those marginalized by their age: children, older and feeble people

-those marginalized because of their gender: women

-those marginalized because of their religion or ethnicity: the Syrophoenician woman, the Samaritan woman at the well

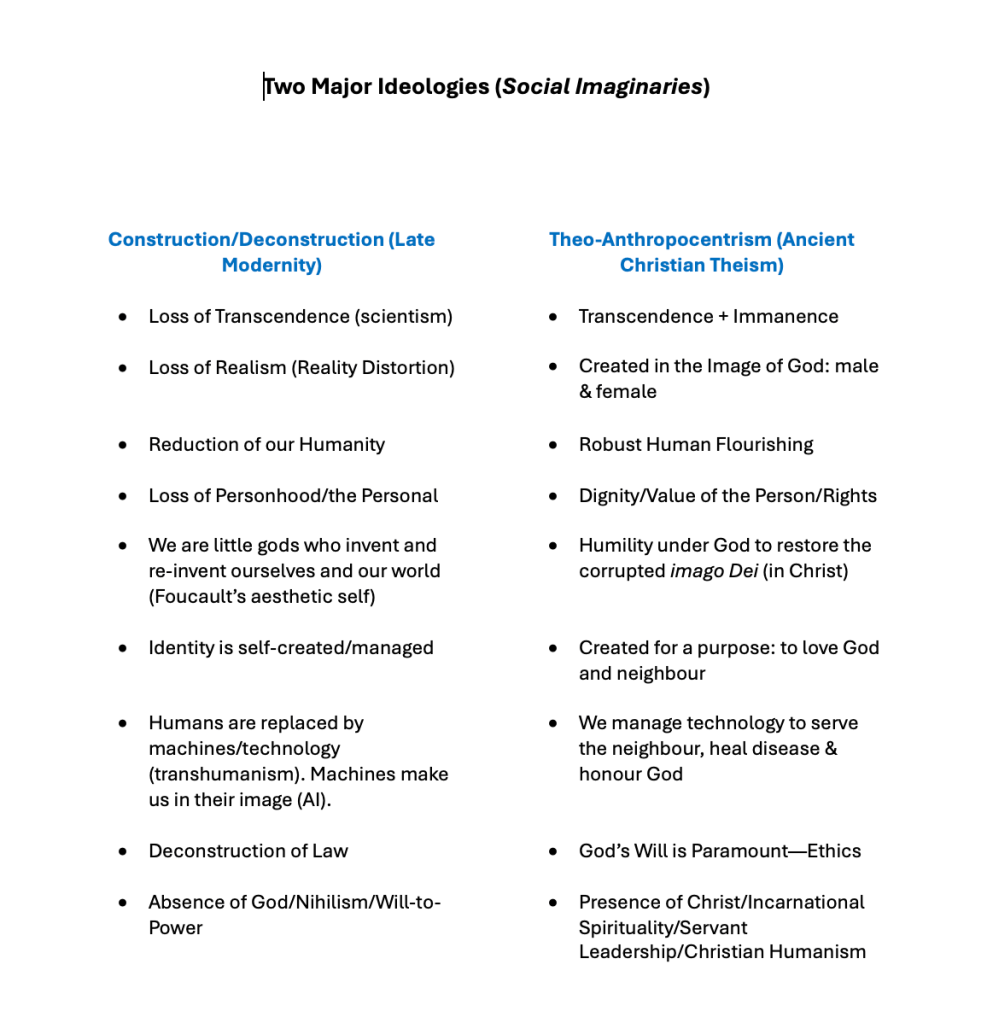

Another Important Category: Social Imaginary

This term comes from Charles Taylor (Modern Social Imaginaries)and has some relation to the concept of worldview: “something much broader than the intellectual schemes people may entertain when they think about social reality in a disengaged mode.” Here’s what Christopher Watkins says, reflecting on Taylor: “It is not a catalogue of thoughts people have about the world, but the ways in which they imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images which underlie their expectations. A social imaginary is a cluster of images, stories, legends, etc. that legitimate common practices. It is not a map of a place, but an implicit grasp that allows me to get around a place in the same way that I can find my way around the house I know well in the pitch dark. Finally, social imaginary is not opposed to theory. Sometimes it is shaped by theories even as it transforms them … and in turn it informs the construction of theories. Another way of putting it is “worlds”, “my world” or “our world.” A world is composed of many different types of figures and is reducible to none. It is a mix of artifacts , ideas, styles, institutions, and attitudes; it bridges narratives, behaviours, laws, and relationships.”

Summary Compared to the big escape from the world and responsibility of Gnosticism, an incarnational spiritual culture articulates God’s story of loving redemption for individuals, families, the culture, and the planet. One is properly human within appropriate limits, but with a high calling under his care to represent him and to steward the earth as imago Dei. We are part of a dedicated counterculture. Jesus is the God-man at the right hand of the Father, interceding for us and our network of relations. He sent the Holy Spirit to gift, heal, empower, and encourage us. He will return to bring fulfilment to all humans seeking spiritual wholeness. His death on the cross remains the climax of God’s redemptive narrative, a model of humble servanthood and suffering love for a broken world.

Other Research in This Field: Incarnation, Critique of Late Modern Culture, Modern Forms of Gnosticism.

Kevin Vanhoozer, Mere Christian Hermeneutics: Transfiguring What it Means to Read the Bible Theologically. Zondervan Academic, 2024.

Jeremy Begbie, Abundantly More: The Theological Promise of the Arts in a Reductionist World. Baker Academic, 2023.

William T. Cavanaugh, The Uses of Idols. Oxford University Press, 2024.

Francis Joseph Hall, Dogmatic Theology: The Incarnation (very important work).

WILLEM MARIE SPEELMAN, “SPIRITUALITY OF THE INCARNATION”, Studies in Spirituality 27, 143-162. doi: 10.2143/SIS.27.0.3254100 © 2017 by Studies in Spirituality. All rights reserved.

Lisa Sung, Visiting Scholar, Regent College, Vancouver, Canada: The Incarnation, Race, and Spiritual Formation.

Daniel Treier, Wheaton College. “Incarnation.” in Christian Dogmatics: Reformed Theology for the Church Catholic, edited by Michael Allen and Scott R. Swain, 216–42. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2016.

Carl R. Trueman, The Rise & Triumph of the Modern Self.

Athanasius, On the Incarnation (a classic)

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part III

Eric Mascall, The God-Man.

N. T. Wright various books on Jesus and Paul’s Writings .

Philosophical Inquiry into the Incarnation (Closer to the Truth) https://closertotruth.com/video/the-incarnation-a-philosophical-inquiry/

Jeremy Begbie, Abundantly More: The Theological Promise of the Arts in a Reductionist World. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2023. (Gospel Coalition 2023 Book Award).

Thomas Torrance, The Incarnation.

Christopher Watkin, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia: Biblical Critical Theory.

Richard Swinburne, The Evidence of Incarnation.

John R. W. Stott, The Message of Ephesians.

Andrew Paul Davison, Astrobiology and Theology: Exploring the Implications of Life in the Universe. Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Eugene Peterson, Practice Resurrection.

Jens Zimmermann, Houston Centre for Humanity and the Common Good: his IVP Academic book Incarnational Humanism.

Sherelle Ducksworth at the Center for Faith & Culture.

Graham Tomlin at the Centre for Cultural Witness (Lambeth Palace)

Stephen T. Davis, Daniel Kendall & Gerald O’Collins: The Incarnation: An Interdisciplinary Symposium on the Incarnation of the Son of God.

Abigail Favale, Notre Dame University: The Genesis of Gender: A Christian Theory.

Anthony Thiselton, Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. 2015.

UBC Grad Student Blog Post on Calling: https://ubcgcu.org/calling/

Sources of Identity Questions: https://ubcgcu.org/2023/12/08/a-life-worth-living/

UBC Graduate and Faculty Christian Forum lectures: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCl4NgIg_ht8IZCRIhho4nxA Website: https://ubcgfcf.com

Modern Expressions of Gnosticism: Douglas Geivett and Holly Pivec at Biola University in California (Holly has a regular blog on NAR) + André Gagné at Concordia University in Montreal, a specialist in religion and politics.

Can We Allow the Philosophers to Speak? A key question is raised by the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, “What do I find in my deepest core to be true?” On reflection, he saw the answer as self-sacrificial love (agape), as found in Jesus of Nazareth. For Kierkegaard, God was his sole way out of anxiety and despair–the trap of ‘aestheticism.’ Here in agape was the truth that edifies. Another significant philosopher, Immanuel Kant, especially in his third tome on practical reason, saw that the existential human need was for justice, i.e., for the moral good to prevail. Only a being such as an omni-benevolent and powerful God was adequate to secure that guarantee. There had to be a cosmic will and a transcendent, radically other goodness to source and inspire human goodness. I have argued in this book (especially chapter 5.) that this works within the culture of incarnational spirituality. This source of the good in God would lead us to treat others as an end in themselves, rather than a selfish means to our ends. I remember one more philosopher who noted: “God from ancient times (Plato and Aristotle) is the central explanatory concept. If you don’t understand this concept, you don’t understand the first thing about the world. Even the notorious atheist, Friedrich Nietzsche, recognized this truth.” (G. Carkner, Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture)

Conclusion: In one sense, the research on the sheer grandeur and potential impact of the incarnation of the Christ has just begun. It is truly unfathomable!

How Can We Navigate Late Modernity?

Dr. Gordon E. Carkner

In my earlier book, The Great Escape from Nihilism, I showed the serious impact of contemporary nihilism on our vision and our culture in the West—it often feels like a prison. It impacts every aspect of life resulting in many young people today with an existential identity crisis. Is there a way of escape from cultural nihilism? Below, I compare two radically different ways of seeing and engaging the world (social imaginaries): a. the epistemological approach; b. the hermeneutical approach. I hold that here is a way out of nihilism and into higher, richer meaning, but we must navigate it carefully. We need fresh vision in late modernity.

a. The Epistemological Way of Seeing

The set of priority relations within this picture often tends towards a closed world position (CWS) within the immanent frame (Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, 2007, chapter 15). Its assumptions include proponents like Descartes, Locke, and Hume. Taylor calls identity as the modern buffered self. We find this approach rooted more in Anglo-American philosophy. The connection between self and world is an I-It relationship. One might also call it the way of disenchantment or reduction of reality.

- Knowledge of self and its status comes before knowledge of the world (things) and others (cogito ergo sum).

- Knowledge of reality is a neutral fact before the individual self attributes value to it.

- Knowledge of things of the natural order comes before any theoretical invocations or any transcendence. Transcendence is often problematized, doubted or repressed—for example, in reductive materialism. This approach tends to write dimensions of transcendence out of the equation as a danger to wellbeing (superstition). Science is hacked by scientism.

- Human meaning is much harder to capture in this frame of reference—leading to disenchantment. Productivity is of the essence. It can cause alienation and lead to skepticism, promote disengagement from a cold, mechanistic, materialistic cosmos.

- Language is Designative (Hobbes, Locke, Condillac)—instrumental, pointing at an object, manipulating objects, and often in turn manipulating people as objects. It is a flattened form of language, which does not allow us to name things in their depth of context, their embeddedness. Poetry, symbol, myth are missing from its discourse. Scientific rationalism is dominant: evidence and justified belief. See Charles Taylor, The Language Animal.

- Power and violence hides under the cloak of knowledge and techne: colonization, imperialism, war, environmental exploitation, Global North versus Global South, East versus West. Hubris, dominance, colonialism is an endemic problem in this view.

- Ethics is left to the private sphere of individual values, because of the fact-value split or dualism—moral subjectivism results. Moral relativism results. This often leads to loss of moral agency and nihilism, partly due to the loss of narrative and the communal dimension of ethics.

- Human flourishing is a central concern within this immanent frame: reduction of suffering and increase of happiness. Health, lifespan, safety, entertainment, economic opportunity, consumer choice are all key cultural drivers. This results in a thin self, focused on rights, entitlements, opportunities to advance one’s own personal interests and agenda.

b. The Hermeneutical Way of Seeing:

The working assumptions of this approach includes proponents like Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Gadamer, the later Wittgenstein, Charles Taylor, and Jens Zimmermann. We find this approach rooted in Continental philosophy. The connection between the self and the world is an I-Thou relationship.

- Self in this case is not the first priority. The world, society, and the game of life come first. We only have knowledge as agents coping with the world, and it makes no sense to doubt that world in its fullness. Taken at face value, this world is shot through with meaning and discovery.

- There is no priority of a neutral grasp of things over and above their value. It comes to us as a whole experience of facts and valuations all at once, insights and desires interwoven.

- Our primordial identity is as a new player inducted into an old game. We learn the game of life and begin to interpret experience for ourselves within a larger communal context. Identity, morality, and spirituality are interwoven as parts of our identity. We sort through our conversations, dialogue with interlocutors, looking for a robust and practical picture of reality—leading to meaning, fruitful engagement, and purpose.

- Transcendence or the divine horizon is a possible larger context of this social imaginary—metaphysics is validated. Radical skepticism is not as strong here as in the epistemological approach. There is a smaller likelihood of a closed world system (CWS, closed to transcendence as a spin on reality or framework of seeing). In a sense, it is more humble, nuanced, embodied, socially and culturally situated within a history.

- Language usage is Expressive-Constitutive (Herder, Hamann, Humboldt, Gadamer) The mythic, poetic, ethical, aesthetic, and liturgical revives offering cultural re-enchantment. Language is rich and expressive, open, creative, appealing to the depths and breadths of the human soul. Language is a sign rather than a mere instrument. See Charles Taylor, The Language Animal.

- Moral agency is revived within a community (oneself as another) with a strong narrative identity, in a relationship to the good, within a hierarchy of moral goods and practical virtuous habits that are mutually enriching and nurturing. The Supreme Good is a motivation for constructive behaviour. One is more patient with the Other, the stranger: hospitality dominates over hostility.

- The focus of human flourishing is on how we can live well, within our social location—a whole geography of relationships that shape our identity, and which we in turn shape as well. This is considered a thick version of the self, open to strong transcendence, within a meaningful whole. (900 words)

https://www.amazon.ca/s?k=gordon+e+carkner&crid=2EKGBFP84YIH0&sprefix=%2Caps%2C141&ref=nb_sb_ss_recent_1_0_recent Amazon LocationDescription: Rooted in the robust discourse of eminent Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor (A Secular Age), this book takes the reader on a journey of deep reflection and discovery. The crucial question we are left with is this: Do we intend to be our own gods in some gnostic permutation—to invent ourselves from the ground up according to our own individual design?