Towards the Recovery of Constructive Ethical Dialogue/Discourse

Let’s talk about the glue that holds relationships and society together. Many people today are discouraged and confused by the moral drift in Western society, wondering if they can have any voice or influence in a world with such a strong emphasis on individual choice, subjectivist approach to values, aesthetic taste in ethics and radical, self-defining (self-justifying) concepts of freedom. Freedom currently in the West is often claimed as an ontological position, a reality within which one can justifiably choose one’s own moral parameters and construct or re-invent the self. In his important book, Sources of the Self (1989), followed by A Secular Age (2007), and The Language Animal (2016), eminent Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor attempts to track and understand the moral soul of early and late Western modernity, especially what he calls the North Atlantic viewpoint. The narrative is a complex one, but vital to comprehend if we are to truly understand ourselves and our friends and colleagues. There are many ideological forces at work today and many experiments in promoting an ethics of happiness, or consequence, or situation, one of pleasure or principle. The focus of ethics can be radically varied.

Religiously-oriented people today can feel powerless and a bit odd, even guilty, for holding any moral convictions at all, that is, besides a consumeristic will that follows its self-interest desires. On this important topic, visiting Notre Dame Early Modern European History scholar Brad S. Gregory has a most profound Chapter 4. “Subjectivizing Morality” in his 2012 publication The Unintended Reformation. Many today feel themselves caving in or abandoning their inherited standards of behaviour under the weight of the cultural slippage–towards nihilistic relativism and radical individualism or autonomy without responsibility. Where can people turn for assistance, discernment, and wisdom on this matter?

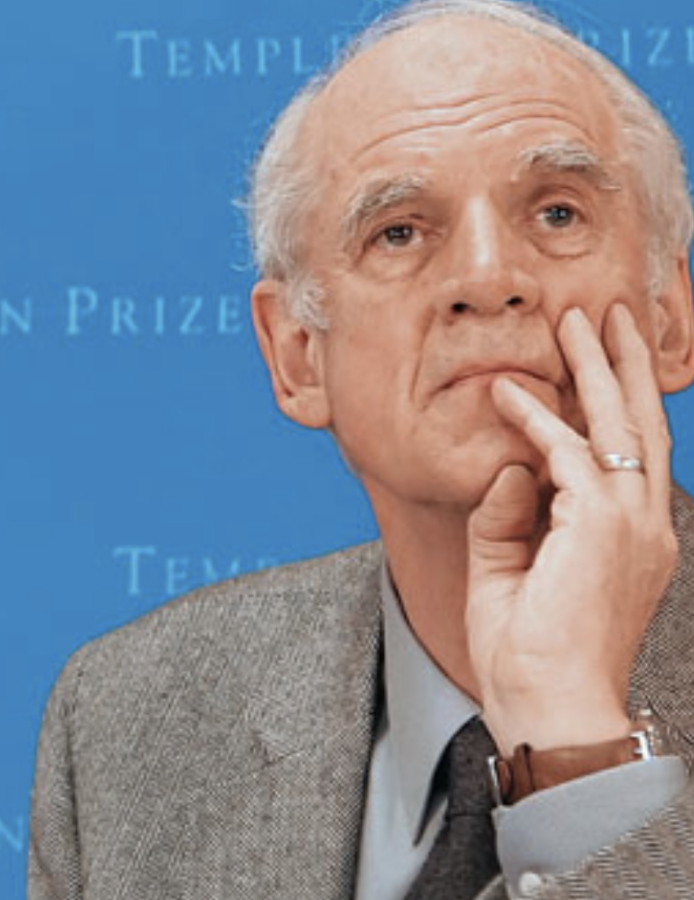

McGill University Philosopher Charles Taylor’s first great tome

In the West, is there any basis left for normativity, for accountability, even for responsibility for the Other? Is it all just about my agenda, my choice, my naked will, my career, or my aesthetic self-invention and personal fulfilment? “What is the quality of this choice, this will?” asks Taylor as he retrieves an ancient idea of qualitative discriminations in ethics–the language of the moral good or goods (See especially Part 1. of Sources of the Self). In what is choice grounded, and how is it guided? We late moderns can be very naive about our Faustian deals when we make expressivism (performativity) an absolute within an ideology of unshackled freedom and self-determination. Post-Romantic philosophers like Michel Foucault offer an Art of Self or an ethics as aesthetics as a morality substitute in an age of nihilism and anomie (transgressive, norm-less existence). Is that our future?

This twelve part blog series on The Qualities of Freedom of the Will suggests that pre-eminent Canadian philosopher of the self Charles Taylor offers himself as a very strategic interlocutor on this issue of freedom in his discussion of moral frameworks as a source of thick identity. He wants to retrieve a robust moral grounding in order to avoid contemporary solipsism (think Julia Roberts in the movie Eat, Pray Love). He believes that these goods can empower us as moral beings once again. They need not remain buried in contemporary moral discourse beneath the fragmentation of our choices, desires and distractions. Following in the footsteps of one of Oxford’s greatest philosophers, Iris Murdoch, this project (Malaise of Modernity; Sources of the Self) entails a dynamic, adventurous and exciting recovery of the ancient language of the good and a renewal of a fresh social normativity–a renewal of robust moral discourse in the polis.

Taylor is highly skilled in employing an engaging language that a pluralistic audience can understand and grapple with, both at the intellectual and practical moral agency level. He encourages us to think more deeply about the qualities of our freedom. It resonates with many people who feel morally lost in a pertinent way. One has to be willing to think harder and go deeper than much contemporary thought on ethics, ideals, and morals. It impacts our politics as well. I want to attest to the fact that it is worth the effort, and the grappling with unfamiliar vocabulary. It offers fresh hope for Western pluralistic cultures and sub-cultures. This is definitely part of the Western intellectual heritage, The Great Conversation.

The following series outlines his monumental contribution to moral and ethical thinking (the ontology of the good). It reveals a phenomenological aspiration to the good inherent in most humans if they are willing to reflect more circumspectly with Taylor. He proposes an aspiration which can be a robust challenge to the ethical solipsism and Zarathustra will-to-power outlook so common in culture today.

What are the valid and sustainable parameters of our current moral quest, our current quest for freedom, wholeness, identity, happiness? Within our various spiritual journeys, the quest for meaning and identity impacts our lives existentially. How do we map this language of the good in today’s world and put it to work for positive change and for higher meaning and purpose? Taylor as a philosopher is an avid moral geographer. Moral ontology is deeply important and central to all other discussions about the moral self. It offers real insight into the inner landscape (deep structure) of the self. Therefore it remains central to engage the current debates of our day in the midst of a loss of moral consensus, as astutely noted by brilliant philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre (After Virtue). Moral autism (inability to speak and articulate morally) and relativism is not an acceptable or stable place to rest for our future wellbeing. It will lead to bigotry, oppression, and violence, says Bishop Lesslie Newbigin (a formidable UK intellectual).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5XC6DK1WkR4 Conversation (2012-06-16) with Charles Taylor rooted in A Secular Age (his Templeton Prize winning tome).

I trust you will enjoy reading and reflecting upon, perhaps debating with me in this series of posts.

Gordon E. Carkner, PhD Philosophical Theology, University of Wales, Meta-Educator with Postgraduate students and faculty at UBC, author of The Great Escape from Nihilism; and Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture, Champion of The Great Conversation.

PhD Dissertation: “A Critical Examination of Michel Foucault’s Concept of Moral Self-constitution in dialogue with Charles Taylor.” Find it in the British Library in London, Oxford University Library, or Oxford Centre for Mission Studies Library.

More Great Resources: On the recovery of substantial ethical discourse, see also Notre Dame sociologist Christian Smith, Moral Believing Animals; plus his more recent book: Atheist Overreach: and R. Scott Smith, In Search of Moral Knowledge: Overcoming the Fact-Value Dichotomy. IVP Academic, 2014; Houston & Zimmermann (eds.), Sources of the Christian Self. Eerdmans, 2018.

.

Yoho National Park in Canada, a World of Wonders